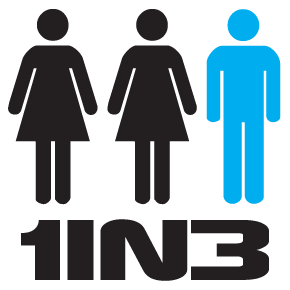

1IN3 Podcast Ep.005: Intimate Partner Abuse of Men Workshop - Part 4

We feature highlights from the Intimate Partner Abuse of Men Workshop held on Wednesday 16 June 2010 in Perth, Western Australia. The workshop was aimed at service providers plus anyone who works with victims and perpetrators of family and domestic violence, and considered the implications for service providers of the Edith Cowan University (ECU) Intimate Partner Abuse of Men research.

In this, the fourth part of the workshop, we listen to a Question and Answer session between the audience and the ECU researchers, Dr Greg Dear and Emily Tilbrook.

MC: We do have a few minutes for questions before we go to morning tea.

Q: My name’s Maggie Woodhead and I’m from the Department of Health. It’s a -- what struck me in the barriers to disclosing was first of all, the similarities, you know, that women also say those things, but within that, there was a key for me, a key standout thing that wasn’t there which was a fear, a terror, of what the partner would do to the victim if they found out that they’d disclosed. And that’s led me to wondering what working definition you had as to what you - and I know it’s grounded research and I understand all that, so you took a lot from – you took the definition from what they were telling you. But I’m wondering you know, sort of, did you have the background within yourself of knowing that, as you said, initially that domestic violence is an ongoing you know, sort of reign of terror designed to intimidate and control. And if it is that, then you have to have as the key – well one of the key barriers to disclosing I would have thought - that fear of what the other will do if they find out. Can you talk a little about that?

Emily Tilbrook: It was something that we were aware of. We’re obviously familiar with the literature in the area, so we were aware that the theory of intimidation and power and control elements are there. It was something that a few of the men mentioned and a few of the men mentioned it in regards to their experience more so than in barriers to disclosure, but some did mention it in barriers to disclosure. But the other themes were much stronger, which is why they’re in the report. There was only a couple that mentioned it in the barriers, whereas others had mentioned it in the experience area. So, “this was my experience,” but it wasn’t necessarily something that they specifically mentioned as a barrier for them. But they did mention it; a couple of them did mention it as a barrier. So, it’s something that men are also often reluctant to talk about, experiencing fear. And they don’t necessarily use the same words. That’s one of the things that I noticed when I was doing the interviews, they don’t necessarily use the words. That’s something that we actually want to research a little bit further because they don’t actually necessarily use the words “fear” and “intimidation.” They might use “worry” or “concern” or, “I was deeply concerned about that” or “I was very worried about that.” So, I think that’s something that needs further research actually is how men define – talk about the experience of fear. Have you got something to add?

Greg Dear: Yeah, I think that as Emily has mentioned, that is something specific that we are wanting to do further research on and drill down into, because down the track there needs to be the sort of epidemiological research that talks about prevalence and range of experiences, etc. if for no other reason than for service provision and planning. I think we need to understand the way that men not only experience fear, but more importantly, how they articulate it. And I’m reminded of – I’ve done quite a bit of research in the prison system and particularly with vulnerable prisoners and around self-harming behavior and suicide. And I remember in one study, we just had to drop the part of the survey that related to anxiety and fear because no man in prison knows what fear is.

Well, doing a more in-depth conversation with them around their experiences, in particularly around the bullying and – I mean bullying is a euphemism for some of the power and control and terrorising that goes on amongst the men in prison from time to time. But yeah, you give them a simple sort of checklist that might work with another victim group and you think, “oh well, these guys have got nothing to worry about, they’re not worried.” It’s about how men and particular subgroups of men articulate those experiences, whether they recognise them. Whether – I think Emily, in one of her conversations with me about one of the men who spoke about fear and intimidation, she said, “It was really hard for me not to sort of drop those words in the conversation even though I could sense that’s what he’s talking about. But luckily, eventually, he did. But every time he got close to talking about that topic, he’d distract himself by talking about something else.”

And I think it’s something that we need to understand much, much more because we run the risk of misleading ourselves if we try and work that issue into prevalence studies without knowing, what’s the reliable and valid way to collect that information from them? So, they’re not all just ticking the box because they think they should, but they’re not avoiding to tick the box because they don’t recognise it or know what words to use.

Q: My name’s Vlasta Mitchell from the Fremantle Multicultural Centre. I was just wondering, well I was surprised that one of the barriers that was identified wasn’t “hope” because maybe that came up in other ways, but we actually find at the centre that with both male and female victims of domestic violence that it’s the hope that things will change, the hope that if we work out why the perpetrator is behaving in this way, and I know that that’s come up with some of the significant others, that the victim might be more interested in what the issues are for the perpetrator rather than for themselves. So maybe inadvertently that was covered there. But I was wondering if it actually came up as an issue that, it could be financial stress, or a new baby or something that is causing the perpetrator to behave this way and once that situation is resolved that the violence will stop and that people just get into a pattern that it’s never resolved because the hope is always an underlying issue. Did that come up at all with some of your interviewees?

Emily Tilbrook: Not specifically those words. I would say that – what was it that you just said then? Greg?

Greg Dear: It probably came up more under the theme of denial and minimisation.

Q: I was thinking that might be the case when I was reading the report. But to me, I would see denial as a non-recognition that it’s going on at all, whereas, these people that we work with, they say, “yes, we are being treated in this way.” So, it’s not a denial at all, they are actually accepting that this is actually going on, but that it won’t go on forever because things will get better in the situation which will mean things will get better in the relationship.

Emily Tilbrook: I suppose that came up in the themes of trying to protect the perpetrator and the family unit. That was something that had come up, you know, wanting to keep their family unit together, which I guess is, they didn’t necessarily talk about it in terms of the word “hope”, but wanting to keep the family unit together which suggests that there is some hope there that the family unit can stay together and things will get better, yeah. But that’s still obviously another area to look at.

Q: Thanks. Ross Moody, I’m just a ring-in today. I’m interested in the statistical significance of the study. I’ve read the study and really interested in the outcomes, but is there a question of statistical significance with only 28 people being involved in the study in terms of victims?

Greg Dear: The word “statistical” is irrelevant to the first study. It’s not a statistical exercise. The relevant methodological consideration is about whether or not we have saturation in our data. Now, what that essentially means is, if we keep talking to more and more people, are we going to get new themes? We will get different variations on those themes, we might get some better quotes to put in, but are we going to learn anything about the broad issues, anything new about the broad issues? I mean, our last question suggests that, you know, maybe there are more themes out there, but we had certainly reached the standard criterion for saturation in our data with much less than the 28. This sort of exploratory grounded theory research often has sample sizes more around sort of 10-15, so it’s actually a large sample for that sort of study.

Statistical significance I suppose becomes relevant in the second phase where you’re looking at quantitative data, although we didn’t – we haven’t done any statistical analyses of looking at differences between groups, like between different categories of service provider – were they more likely to see this type of barrier or that type of barrier. That weren’t really the questions that we were interested in. We haven’t – I suppose we could go and drill down into our data in that sort of way and do some chi squareds. Certainly the sample size in the survey is large enough to enable some of those sorts of analyses.

And then 103 service providers from W.A. and just under 100 from around the rest of the country and similar proportions when that drops down to 122 who completed the whole survey. We’ve got enough of a sample size to generalise from those data. And certainly there was diversity in the qualitative data and that larger sample of service providers, by and large reinforced, with some important additions, such as you know, the study one, they didn’t build specifically into the definition of what they meant by domestic violence being intimidation, power and control whereas, probably about a third or more of our service providers made the point that that’s important to actually put into the definition. I’m not quite sure what the other two-thirds were thinking, but anyway, maybe they just didn’t think it needed to be said.

I think it’s important in the first study that really what we’re doing here is we’re trying to capture the experiences of male victims, now partly from a small group of service providers who take a keen interest in the issue and partly from significant others and I think the significant others was a particularly important, although small, part of our sample of 28.

I mean, for example, the sorts of data – the themes that Emily was reporting about - “what do you think leads her to be abusive towards you?” Look at the explanations they’re giving? It’s all about mental health or situations, stresses, etc. You often get that when you talk to victims of family violence about what causes it. They talk about including what I might have done to bring this on. That doesn’t necessarily mean that that’s the theory that we subscribe to: that’s the understanding or the perception that’s in the minds of the victims and significant others that we spoke to.

MC: Thank you, please join with me in thanking Greg and Emily again.