1IN3 Podcast Ep.001: Interview with Dr. Greg Dear

Dr. Greg Dear is Senior Lecturer in Psychology in the School of Psychology and Social Science at Edith Cowan University (ECU) in Western Australia. Greg is the co-author, along with Professor Alfred Allan and Emily Tilbrook, of Intimate Partner Abuse of Men, a research project commissioned by the Men’s Advisory Network and released on 26th May 2010.

In this in-depth interview with Greg Dear, Greg Andresen discusses the findings and implications of the ECU research.

Greg Andresen: I’m speaking with Dr. Greg Dear, and Greg is the Senior Lecturer in Psychology in the School of Psychology and Social Science at Edith Cowan University in Western Australia. Greg is the co-author, along with Professor Alfred Allan and Emily Tilbrook of Intimate Partner Abuse of Men, which is a research project commissioned by the Men’s Advisory Network and released on the 26th of May, 2010. Greg, thank you for talking with us today.

Greg Dear: Sure, no Problem.

GA: First of all, can you tell our listeners about the aims and objectives of the research?

GD: Well, I suppose in broad terms, the aim was to collect men who report being victims of intimate partner violence, to collect rich data about the nature of their experiences. In other words, what sort of violence they experience from an intimate partner, or have experienced, how it has impacted on them, and more specifically, what sorts of factors have influenced their decision to disclose that abuse, or not to disclose that abuse to other people.

We were particularly interested in understanding the difficulties that men have in disclosing abuse to service providers in a range of categories.

GA: Okay, so it was very much a qualitative project.

GD: That was certainly the first part of it, and I think the important part of it. The second stage was a survey of service providers where we sought to quantify, I suppose in some way, their views on the data that we had collected in the first stage of the study. In particular, the degree to which they recognised in men who they’ve worked with, the types of barriers to disclosure that we identified in the first phase of the research.

GA: Well, let’s talk a bit about stage one of your research, the qualitative interviews with the male victims, but also with significant other people in their lives and some individual service providers, I believe, who had helped male victims. What different forms of abuse did you unearth in stage one when you talked to these people?

GD: One of the questions that we asked in the interviews was a broad open-ended question about, “when they say they’ve been victims of abuse, what did they mean by that?” How do they define abuse? What are the sorts of experiences they’ve had? And then we’ve thematically analysed the conversation that followed from that opening question.

I make that point because we were quite deliberate in not wanting to give a sort of checklist of the definitions that exist in the literature or the way that intimate partner violence is categorised into emotional abuse, or social abuse, or physical abuse, etc. We really wanted to just get a free flowing conversation of what do the men, and family, friends, significant others of men who reported abuse, what do they mean by that? What is it that they have experienced? What are the behaviours that have been done to them? And what’s their understanding of, more broadly, what abuse might entail, so it would be beyond just what they’ve experienced.

And when we analysed those data, they fell very nicely into the same sorts of categories and definitions as exist in the literature already, so all of the social abuse, financial abuse, pretty much the same way that these are defined in the literature. And an additional category that emerged, and when I say additional, there is some limited research on this and discussion in the literature, but it’s not universally recognised in the taxonomies that people use in the literature. And that was the category of what we call legal or administrative abuse. We sort of struggled in how to label that. And that was the use of legal and administrative processes to control, intimidate, and abuse the man.

GA: And what sort of – can you give some examples of these sort things?

GD: Actually, probably a good thing to do to answer that question is to go to some of the – let’s see if I can find some of the quotes that will illustrate that.

GA: Actually, I think I’ve got one here. This is reading from the report – “You know, I haven’t said hello to the lady, yet alone been anywhere near her for more than eight years. Why am I being served with a VRO? You have to like, sacrifice so much effort to prove yourself innocent. It is ridiculous and a lot of men just aren’t – they can’t cope with it.”

GD: Yes, I mean, that’s a classic one. Another one is, well there’s quite a lot of references by some of the men to the use of various proceedings in Family Court. And there’s some interesting ones as well about – with immigrant men, and a couple of the service providers mentioned this, where the wives will threaten to withdraw the sponsorship. So, if you’re a sort of non-Australian resident who has come here with a partner, either married or defacto who isn’t an Australian citizen, then you come here as a sponsored immigrant. And the sort of threats to remove the sponsorship so that he will be deported.

So there’s a range of – I mean, another example that comes to mind that isn’t quoted in the report was the anecdote by one of the male victims we interviewed who told about an occasion when he actually called the police because she was basically throwing things around the kitchen. And she wasn’t directly physically assaulting him, but he sensed that what was coming next was that she would start throwing objects at him. And the children were there witnessing this, so he phoned the police, who duly arrived, and took her and the children to protect the children from him because when the police arrived, she gave a different version of events to him. And the police, their automatic assumption was that the children were at risk from him, rather than at risk from her. So, she and the children were – well he doesn’t know where they were taken, but we can assume a refuge.

So, these are example, if you like, at least this is what the men tell us. These are examples of how a female partner uses legal and administrative systems that are in place to protect people who are at risk of violence and deliberately misuses them in order to gain power in the relationship, effectively.

GA: I’m just going back to an earlier point that you made about letting the men tell their own stories in their own words, rather than putting a checklist there or even asking them, you know, “have you been a victim of domestic violence or have you been a victim of intimate partner abuse?”

GD: That opening question was asked of them because really, we were quite deliberate in seeking people, you know, advertising for people to contact us and participate in research to tell us about their experiences of being abused by a female partner, or by an intimate partner.

GA: Okay, so the specific question was asked, but then in terms of the sorts of experiences they had, they were then free to elaborate.

GD: Yes. So any man who contacted us and said, you know, “I’ve heard the radio interview that you did or I saw the flyer on wherever, or I saw the ad in the community newspaper.” And I’ve been a victim of abuse from a partner, well then we would take that on face value and the opening part of the interview was really asking him to explain what he means by that. What is the abuse that has been done to him?

GA: I guess the question I’m getting at is, whether – do you think you might have actually missed some men in recruiting research subjects by specifying domestic abuse in the sense that, do you think that some men may not identify their relationship experiences as domestic violence or abuse the way that possibly women may have been more educated to identify those experiences? So for example, if their partner is, you know, not giving them access to the funds in the house, or whatever, that women may be more likely to think of that as domestic violence or abuse and men may not and therefore may not have called up to take part in your study? Do you think that’s an issue?

GD: I think that’s a huge issue. I was about to say I have no doubt, but I don’t know if I can substantiate that assertion. So let me put it this way. I’m confident that many men who would have been good participants in our research would not recognise that they are the victims of abuse. And so would not have responded. It was, in fact the theme that came through our data from significant others who we interviewed. And I mean, that was something that we expected, and it was part of our rationale for including significant others in the study - a deliberate part of the design - because we thought it might be the case that very few men would put their hands up if they do recognise themselves, that other men would fail to recognise what they are experiencing as intimate partner abuse or domestic violence, but that other members of the family who are aware of it might recognise it as that.

It’s interesting that the – all but one of the significant others who contacted us were women who might be, like the current partner of a man who was abused by a previous partner, the man’s sister who is aware of what is going on, or has been going on in the relationship, and in one case, the one male significant other was talking about the relationship between his parents and his mother’s psychological and physical abuse of his father. And a strong theme coming through the significant others was that the men don’t recognise that what’s happening to them is domestic violence. They recognise it as abusive and wrong and, you know, they would like it to stop, but the label of domestic violence is something they either refuse to put on their experience, or just fail to conceptualise it in that way.

And then the service providers echoed that same theme to some extent as well. And indeed, one of the barriers to the disclosing is men’s failure to recognise it as domestic violence, or their reluctance or refusal to see it in those terms for a whole variety of reasons.

GA: Do you think that one of the causes for this may be, I guess, an unintended consequence of community education campaigns that we’ve had over many years which have done a great deal in terms of raising the awareness of the issue of domestic violence for women; do you think one of the unintended consequences of that might be that some men might think that domestic violence is something that happens to women, and therefore, you know, what I’m experiencing can’t be domestic violence?

GD: It’s entirely possible that that’s part of it.

GA: Would you hazard to guess as to what other things may be behind that? Is it something about men’s sense of masculinity, or –

GD: That was a strong theme coming through our data. And in particular, I think, that – and I’m going beyond our data here and sort of hypothesising, but I think is behind the sort of reluctance to label it as domestic violence and sometimes the, what significant others described as, you know, he just outright denies it even though, you know, in one sense he knows it’s happening and talks about it, but you know, denies that it’s domestic violence.

I think part of it is around issues of masculinity, and that was a strong theme in our data, that related to the shame that men experienced. The difficulty they have in admitting it to themselves first of all, and secondly, disclosing it to service providers. That’s, you know, men are tough and men can cope in a bit of push and shove and all the rest of it, you know.

GA: They’re supposed to be able to take care of themselves and all of that.

GD: Yes, we take care of ourselves and we’re tough and all the rest of it. But, beyond those sort of, I suppose, stereotypical masculine constructs, it was a sense that people out there aren’t going to understand or believe what I’m going through because it doesn’t fit – it doesn’t fit the mould. It doesn’t fit the definition of what is meant by domestic violence. So I think that’s where the issue that you raised might come into it.

GA: And did some men actually have experience of this? For example, going in to the police station and not being taken seriously? Or –

GD: Yes. Absolutely. There’s a couple of examples of that that we quote from in the report. In fact, one man who reports that he went to apply for a domestic – actually no, it was a significant other who reported this in the interview. She accompanied, I can’t remember who it was, her brother or something. Anyway, she accompanied the man into court when he was applying for a Violence Restraining Order against his ex-wife, I think it was. And, well according to what the significant other told us, the Magistrate said, well you know, this guy is apparently quite tall and not slight, and the Magistrate just said to him, “You’re a big strong lad, you should be able to take care of yourself,” and declined the Order. Now, I find that quite astounding because what I’ve seen in court a lot of times is Magistrates on occasion sort of voicing that they’re not 100% convinced that this is necessary, but a person has a right to demand that someone else leave them alone, so they’ll issue it. I’ve heard that a number of times.

GA: Well, it’s all the more shocking to me, almost the inference of his tone was that, you know, the guy could sort of defend himself, which would almost imply hitting her back, which is, in a sense almost justifying further –

GD: Well, I mean, one could only guess what the Magistrate might have meant by that and whether or not that is an accurate quote of what the Magistrate said, it’s clearly the message that this woman took away from accompanying, I think it was her brother into court. And then her remark was that he walked out of court just feeling even more stupid than he did when he walked in and thinking, well, “if I can’t get support here, who else is going to believe me?” And there are a number of occasions where men reported similar things from the police.

It was interesting that in our, in the second part of the study, quite a number of the service providers recognised this as being an issue that is not just within the men’s perception, that they think they won’t be believed or won’t be supported or won’t be taken seriously, but the service providers themselves were telling us that that’s actually what sometimes happens. And that they have seen that happen. And there are even a couple of service providers who made comments in our survey and, you know, it was largely quantitative, but there were some sections where they could write comments and we took those comments and analysed, a qualitative analysis of that text. And there were a small number of service providers who basically expressed views like, “look, if the man is reporting being a victim of abuse then her behaviour towards him is probably retaliation for something he started himself.”

So, I mean, if people are, service providers are participating in a survey about men’s experience as victims of intimate partner abuse and that’s the comment that they’re making then I think that itself further illustrates what other parts of our data are saying, that the men worry or are concerned that they won’t be believed or supported or indeed that they might even be blamed, that they don’t expect members of the community to understand that this happens to men. A lot of them are ashamed that it has happened to them, feeling less of a man, like a failure, that “this is something I should have been able to prevent or sort out.” And then, as we’ve already discussed, some of them report the experience of not just worrying that that sort of response might occur, but they’ve experienced it. And the service providers are telling us that they’ve seen it occur and then a couple of the service providers are actually demonstrating that in the way they’ve responded to the survey.

So I think all of that adds up to a fairly consistent picture that I think there are problems in the way that the health/welfare/justice field responds to men who disclose being victims and I think it’s a very different response than those same people would give to a female victim.

GA: Or certainly in 2010, it may be a similar response to – and I’m hypothesising here, but it may be a similar response that women may have got in 1950, but thankfully, at least we have service providers now that you would hope would be more sensitive to women that approach them in 2010.

GD: Well yeah. I mean, I’ve worked in terms of my clinical work in the alcohol field and working with families. I’ve worked with many women in the 1980’s and 1990’s who are still getting that sort of response from police. It was the minority rather than, you know, the standard response, and there were quite a few deliberate campaigns and training and other things that the police did across the 1990’s that really improved things. So, you know, we probably don’t have to go all the way back to the 1950’s to find that women were experiencing the same thing that men are now reporting.

GA: But I guess the positives to take out of that may be that if you put the proper training and procedures in place within police and services, etc., that improvements can be made in terms of their education and their sensitivity to the issue. Would you think that that’s the case?

GD: Yeah, yeah. Well, I think that’s very much the case. And I don’t want to single out police here either because, I mean, there were some police officers who participated in the survey and certainly police representatives on our steering committee and other contacts I’ve had with police who specialise in this area, I think there’s actually other sections of the service field in health and welfare areas that probably have a worse track record in this area than the police do. It just happened that the – that some examples that came to mind involve police and courts.

GA: Sure. Look, and I’m sure there are many police officers out there who are genuinely sympathetic and do a very good job. So, yeah I don’t think we should infer by one example that should tar, you know, all the police in that way. But certainly some police officers obviously do need some more training in this area and –

GD: Yeah, one of our key recommendations was really that, across the field, there needs to be a lot more training in relation to responding to men who report experiences of intimate partner abuse, or family violence more broadly. And I think that some of the gender issues I think are extremely important in this. The same way that these sort of gender issues are central to understanding women’s experience of domestic violence. I think one of the important things to emerge from our data is that that’s also the case for men. And it makes sense because all aspects of human experience are filtered through gendered identity of one aspect of the self-concept. Who I am, how I see myself is influenced by my concept of what it means to be a man.

GA: And your biology as a man as well in some sense.

GD: Yes. So, the understanding what it means, and obviously this is going to vary from individual to individual, but in general, what it means for a man to put up his hands, a man in our culture to put his hand up and say “this has happened to me and I’m not coping with it and I want some help” needs to be properly understood by the people who respond to that and men aren’t necessarily going to present themselves in the same way as women might. One of the – and we don’t really talk about this in the report but we sort of reflected on it afterwards, but one of the things coming through quite strongly in the interviews is, it was really after, only after some conversation of the topic that men got to a point where they started to speak about their emotions and about the affects of the abuse on them. And the interviewer really had to sort of probe for that. Like a general question asking about, you know, what are some of the effects of this? Men would initially respond in purely behavioural terms, talking about the event. And it was only by sort of more and more probing that they would eventually get to talking about sense of shame and things like that.

When you interview women about their experience of violence, family violence or other forms of violence, they will move very quickly from telling you what happened to telling you how they feel about it and in richer detail about how it’s impacted on them, on their functioning, on how they see themselves. Women, and this is an over-generalisation, but women move into those topics of conversation more easily than men do. And we know that from a whole range of research topics and research on that issue itself including how men perform in counselling and a whole range of other settings so it’s not just when researchers talked to them.

GA: And what are the implications of that for future research?

GD: Well, I think the implications of that are that it’s like, if men are operating with a sense that I should be tough and I should be able to cope, and I don’t want to present myself as unable to cope, then they will start at that surface level of, “oh yeah, you know, she did this and that’s what happened and you know.” How did that affect you? “Ah, well, you know, my hand hurt for a couple of days but it got better,” or you know, whatever the case may be. And I think men might need a lot more help to actually identify and articulate some of the deeper psychological impacts of that experience. And it is one of the controversies in the field, as you well know, that like, are men who are abused by women, are they intimidated by that abuse? Are they fearful of the abusive partner in the same way that many women are? And I think men and women articulate anxiety and fear and things like that differently.

Now, certainly some of the men in the first phase of our study were able to articulate being intimidated, a sense of being trapped, of being controlled, overpowered, and the impacts of that in terms of, as a man, “I should be better than this, I shouldn’t let myself get into this situation. What’s wrong with me?” So blaming themself for the experience one is having. Now, I’m not suggesting that women don’t experience those things; in fact there’s a wealth of the research said that a lot of women do. But there is some question in the field about, is the impact of a female partner’s violence to a male truly one of intimidation and achieving power and control over the partner; whereas, there’s no doubt that a lot of women are intimidated and controlled by violence or the threat of violence or their perception that there’s a threat of violence. Well our data suggest that at least some men were able to articulate that experience.

GA: In terms of future research, especially large-scale epidemiological research, looking at the prevalence of the quantitative aspect of this problem. Would you recommend against having a tick box for both men and women that said, you know, did you experience fear as a result of your – or if such a tick box was there, would you expect that at least some men would fail to tick that even though they may be experiencing some of the same things that women were because of that language that men and women may use differently in terms of articulating the experiences that they go through as being fearful, or anxious, or controlled or all that sort of –

GD: Yeah. And we’ve been talking about this because when we first – there was a call for tenders about doing this research. And when we first – Alfred and I got together and spoke about, if we were to tender for this project, what approach would we take. The original tender was almost asking for research to identify prevalence of violence against men and we quickly formed the view that we were concerned that, if – and there was already some discussion of this in the literature, that if men failed to recognise what they’re experiencing as abuse, or if they articulate that or use different words, or have a different sense of what abuse means, particularly if they fail to recognise forms of abuse other than physical assault, then we might be thinking we are measuring the same thing as when we ask those questions of women, but we might be failing to pick up a lot of the prevalence. We might be failing to identify cases because we don’t know enough about how men conceptualise this. What are the barriers to disclosure? We were interested in that question because it’s an important one for service providers, but we were also interested because if there are specific barriers to men disclosing, then those barriers might prevent them from disclosing on a sort of written questionnaire type survey.

And so that was why we actually settled for this sort of design, to see if we could understand those issues more thoroughly, not only to guide service providers on, okay, you know, men aren’t going to approach you and put their hand up in the same way that women will. But also to understand that as researchers for – how do we need to design prevalence studies that are going to be reliable and valid? I’ve pretty much come to the conclusion that, if there’s going to be effective prevalence surveys of both men’s and women’s experience, they will be interview-based. Now, I know the ABS one was interview-based, but I’m not sure whether it went into sufficient detail to understand similarities and differences in men’s and women’s experience and prevalence rates.

And I think it’s one of those conundrums where, in order to be able to compare two groups, you want to make sure that you’re asking the same questions, that you’re collecting the same data. So, if you find one percentage in one group and a different percentage in the other, you know it’s a real difference because you’ve measured the same thing. But the conundrum is, sometimes in order to measure something accurately in one group, like in males rather than females, and this is a common conundrum in cross-cultural and multi-nation research where they’re comparing experience in one country to another, that the way to measure something accurately in one culture might require a different approach to collecting the data than in the next country.

And it seems to me at least, that the way to extract the information that you need from men, needs to be somewhat different from the way you extract the information from women. And part of that might be with the point you raised right at the beginning, that women have had a lot of exposure over the years, and rightly so, that enables them or assists them, that a lot of women still have problems disclosing abuse by a partner and for a whole range of reasons. But they have had a lot of experiences and particularly younger women in the way that these issues are dealt with in school education and public campaigns and in support services, in the training of... it’s like the word is out in the whole community that victims need to be believed and supported and there’s no shame in speaking about this having happened to you. Women still feel ashamed, but not to the same degree as they did decades ago to prevent them from disclosing or to significantly delay their disclosing. Whereas, I think, men do feel that sort of shame and they don’t really – certainly one of the things kind of through our data, they don’t have the sense that this is an acceptable topic simply to talk about and admit to.

Plus there’s a whole range of, you know, from a wealth of studies that if you want to get information about people’s emotions and to articulate their feelings, men do that differently than women. I’m reminded actually, in a completely different field, there was some research in the early 80’s on – with problem drinkers and understanding risk of relapse. And there were some very good studies that seemed to indicate that for men, relapses were precipitated more by situational things. In other words, you know I mean an example of a situational trigger of relapse might be that everyone at work is going out for drinks on a Friday and you’re in that situation where everyone’s drinking and you’re the odd one out. And you know, before too long, you end up joining in, etc. So, that’s the sort of high risk situation for problem drinkers trying to give up drinking.

Women’s relapses were, more often then men, triggered by mood states and experiences. So, for women, it might be, when I’m depressed and bored and get those thoughts of self-loathing and you know, that I’ve wrecked my life already, so –

GA: So I might as well have a drink.

GD: Yeah. I might as well – you know, I’m feeling like crap so I might as well have a drink. So there was a lot of emphasis on well, we need to do quite different things in relapse prevention with men than in women. We need to teach men how to deal with high risk situations and women how to deal with their feelings. And sort of focus – Well, then there was some other research that looked more deeply into those issues and found that men relapsed in those high risk situations when they were feeling bad. But unless you really persist, you don’t get that information. Plus, with women, it wasn’t any time I’m feeling bad, but when I’m feeling bad or I’m in the wrong sort of situation. And the end result of probing more deeply into men’s and women’s experiences was that both men and women tend to relapse both in terms of situational and internal mood states and other internal, you know, attitudinal and, you know, the wrong sort of thinking. And it’s the combination of situational and psychological factors that runs a higher risk of relapsing.

GA: But a superficial examination means they actually come out – they describe their experiences in different ways.

GD: Because men will focus on where they were and what was happening when they did it and women will focus more on how they were feeling when they did it rather than the situation they were in.

GA: Greg, in terms of you research; what are some of your suggestions in terms of things that could be done to help male victims become more willing to report their abuse?

GD: This is a bit of a big picture issue, if you like, but really what the conclusion that we came to and why we made the – we could have made a hundred specific recommendations and some of them would have been probably going beyond our data, but in the end we settled for four broad recommendations.

GA: Do you just want to outline those recommendations, to start with?

GD: Yes. Because the first one really gets to the heart of your question and if I read from the report here, the first recommendation was that government funded public awareness campaigns be conducted to raise awareness of intimate partner violence against men. Such campaigns need to be very carefully designed to complement campaigns about family violence against women and children and not to damage the effectiveness of those campaigns.

Because really, the key issue for the men was not only their own sense of shame and difficulty in admitting it to themselves that this is what is happening to them, but their perception, and quite likely an accurate perception, that other people wouldn’t understand what they’re going through or might not believe it or might not be supportive in their responses.

GA: Or may blame the men themselves.

GD: Or even worse might even blame them. And I think one of the men actually made a comment along the lines of that one of the first people he disclosed it to said, “well what were you doing to make her do that to you?” Now, all of us who work in the field know how wrong it is to say that to a female victim. But why did someone in the health service say that to a male victim?

And another one of our recommendations is about training for people working in health and welfare and justice fields. But it really needs to start with a community awareness campaign that puts this conversation about this does happen to men, to some men. How do we understand it, what do we do about it, and to really put it out there as a topic of discussion in the general community the same way that violence against women and children is, because that frees up men to be able to talk about it themselves. It’s not going to suddenly, magically, you know, make men stand up in any public venue and say, “Hey, by the way, did you know what happening to me?” Of course it’s a sensitive issue, but it was a major factor in preventing or delaying men disclosing their experience, the sense of this is something that’s not talked about, it’s not recognised, that no one would understand it, and the sense of shame and the sense of having failed as a man to have this happen to you.

GA: A colleague of mine works with young men in a mental health service. And these are men, high school and just post high school. She did an informal survey and found that all of her young male clients were experiencing some form of family violence or abuse. But this is often from parents, from siblings, maybe step-parents, and other family members. So this is, I guess, broader family violence, not intimate partner violence. Though it may have been in some cases from their dating partner. Do you think that more specific research is actually needed into the impacts of other forms of family violence besides domestic violence upon men, especially young men?

GD: Oh, look, particularly upon young men. I mean, a consistent finding across victim surveys and research into violence shows that adolescent and young adult men or adolescent and young adults both male and female, are the major demographic, if you like, for being victims of violence as well as being a major demographic for being perpetrators of violence. We were disappointed that we had no men under 30 participate in our study. But our study was really limited to those men who recognised this experience in themselves and made contact with us and there’s a whole range of reasons why men over 30 might be more likely to do that than men under 30.

GA: It was also limited just to intimate partner violence as well, I guess.

GD: Yes, yes. Exactly.

GA: There might be a lot of young men, the violence they experience may be you know, at the pub or the sporting field, or lots of other different contexts.

GD: Absolutely. But even if you look at the ABS –

GA: The Personal Safety Survey.

GD: – survey, there were higher prevalence rates in both men and women at the younger age groups.

GA: Certainly the recently released Scottish survey found the same. The big question I guess, one of your recommendations is that community education programs can be designed so as to raise the profile of male victims and intimate partner abuse amongst the general community, but at the same time, and this is really important, not diminishing the profile of female and children victims. How do you think that would best be done? Because I think a lot of people may have genuine concerns that if we start putting the spotlight onto men, that we might forget about women and children. So, how do we do that in a unified way that also teases out the gender differences that are here and not just lumping all victims together as one?

GD: Yeah. Look I don’t have an easy answer to that one. I really think that needs a lot of thought, a lot of debate. I think what we’re doing, what websites like yours are doing, what some of the, you know, media interviews that we’ve been doing over the last few weeks. A lot of interest in this study amongst the media in WA and indeed some of the national media as well, I think is important about getting the message out there. I don’t have a clear answer to that one and really we were quite careful in some of our recommendation talking about this is an issue that governments and policymakers need to seriously consider. And we worded it more in that way rather than, you know, this should happen. Because I don’t think we actually really know enough about how to do that.

GA: So in a sense, your research is almost starting the conversation, which can then sort of roll on, lead to more research, have a discussion amongst the community and maybe eventually we will end up with more targeted or detailed solutions, right? Was that in a sense why you left things as more general recommendations?

GD: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, it would be going too far beyond our data to say, okay, the way this needs to be done, you know, a public campaign needs to say this rather than that, or services need to be designed in exactly this way.

I think our data was deliberately exploratory because we didn’t want to be limited by making assumptions as to what the issues are. We really wanted to just map out, I suppose, what the issues are in terms of men’s experience. And there’s a lot of follow-on research and debate that needs to happen as to what does this all mean and what do we do about it. Our recommendation about public awareness campaigns was very much guided by the fact that, and this is my own words rather than – well, no I think a couple of the men did actually use, if not this word, then something similar to it. But men are isolated in that experience. They don’t have a way of understanding and explaining and accepting that, okay, this happens to men, so they think there is something wrong with themselves. And they’re very isolated in that experience because they don’t expect other people to understand it. So it’s something that they can’t talk about because they don’t know how to articulate it. And they don’t expect other people to respond appropriately to it. So they’re sort of, well, isolated, is the word that I’m using. To put the issue into the public domain lessens that isolation. And it’s my view at least, even thought I’m going beyond our data somewhat, that until we do that I think the sorts of barriers to disclosure that our study identified will be very difficult to break, even if we train service providers.

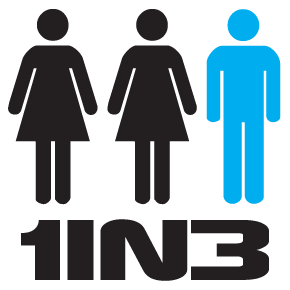

GA: It’s certainly been one of the – it’s probably the strongest theme in the emails and letters of support that we’ve been receiving since we started the One and Three Campaign is that men say, “Finally. I know I’m not alone. Finally there’s an organisation that speaks for me and talks about my experience and I can see that other men are going through this.” And that overwhelming relief - and that has actually triggered them to write in and tell of their experience. So, it’s very, I think, cathartic and really releases that sense of isolation for these men. I couldn’t agree with you more in terms of the experience we’ve had in the One in Three Campaign.

Look, Dr. Greg Dear, it’s been an absolute pleasure chatting with you today. All the best with your work in the future. Are there any plans for follow up studies from yourself or your colleagues, or is –

GD: Well, one of the other co-authors, Emily Tilbrook, who was our research assistant on this project, she did all the interviews, she’s doing her Ph.D. in this area, so there will be sort-of some sort of follow on with her research that she’ll be conducting in that area.

GA: Great.

GD: And I both Alfred and I and other researchers, this part of our group here in Psychology at ECU are certainly looking towards what are the specific projects that we can do next? I mean, ultimately we would like to do the sort of large scale prevalence study and as much as it will be horrendously expensive –

GA: And take a long time in analysing etcetera –

GD: Yeah. I think face-to-face interviews that are constructed so as to engage men in the conversation and then also engage women in the conversation. Now the way to engage them in the conversation might have to be slightly different as long as the sort of data that anchors into that conversation is comparable and the way that you code it or quantify it so that we can have more reliable and more detailed data on the prevalence of men’s experience and women’s experience. Both as perpetrators and as victims. I think it’s interesting that I’ve seen – I think I first saw this about 20 years ago, but that was an isolated observation, but I’ve seen it quite a bit in the last few years in the mainstream and the feminist literature on domestic violence a real sense of, we need to get serious about understanding female perpetrators. And so I think my sense is, that there’s a whole lot of factors coming together in society and in the research community and in the service community that they’re probably all coming together at the same time to really move this issue along rather than have the sort of arguments that people have had in the past. That somehow identifying men as victims will damage the capacity for people to recognise women as victims.

GA: Moving beyond the politics which have probably halted the progress of dealing with this issue, you know, over the decades.

GD: I suspect so, and some of that might be reactions to real threats –

GA: Of course.

GD: – but my sense is that there is a real maturity in the field that will help us move beyond this and look at family violence in all its forms more comprehensively, in a way that will include female to male violence as well as all other combinations.

GA: Well, that’s a great positive note on which to end our chat today. Dr Greg Dear it’s been an absolute pleasure chatting with you and all the best for the future.

GD: Thank you. I’ve enjoyed it as well.