How gender bias in research and the use of misleading language harms male victims of family violence – a case study

Male victims of family violence have always lacked the services and support available (many would say insufficiently available) to female victims. Thankfully more services and support are now available to men than were provided decades ago, however lack of services for male victims is still a significant problem that needs addressing.

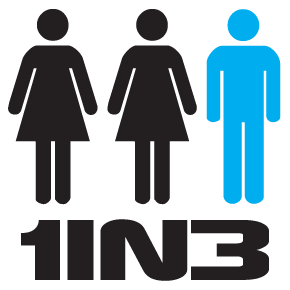

The One in Three Campaign has appeared before many state and federal family violence inquiries over the past 12 years. Despite the vast majority recommending better services and support be provided for male victims, such support has failed to materialise on the ground. The main obstacle to the provision of support to male victims is the “gendered violence” paradigm that dominates the domestic violence sector: the claim that male victims don’t exist in sufficient numbers, or that the impacts on their health and wellbeing aren’t severe enough to warrant the provision of services and support.

This article uses a case study to examine how, despite the good intentions of researchers and publishers, an exclusive research focus on men’s violence towards women along with the use of carelessly misleading language can be harmful to male victims of intimate partner violence by inadvertently propping up the “gendered violence” paradigm and thus preventing men from receiving the services and support they need.

In May 2017, Dr Emma Fulu, PhD, and her colleagues published a study titled Pathways between childhood trauma, intimate partner violence, and harsh parenting: findings from the UN Multi-country Study on Men and Violence in Asia and the Pacific. This multi-country study interviewed men and women in Asia and the Pacific. Male respondents were asked questions about their perpetration of intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence, childhood trauma, and harsh parenting (smacking their children as a form of discipline). Female respondents were asked questions about their experience of intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence, childhood trauma, and harsh parenting (smacking their children as a form of discipline). The researchers explored associations between childhood trauma and violence against women.

Male respondents weren’t asked about their experience of intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence. Female respondents weren’t asked about their perpetration of intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence.

As men’s violence towards women arguably leads to a greater burden of disease than women’s violence towards men (or violence within same-sex relationships), and as research funds are limited, it may appear reasonable to limit the focus of such a study to men’s violence towards women. Even if the research questionably takes the gender-balance of intimate partner violence as a given, rather than seeking to explore it further.

Presumably using a similar rationale, most other researchers in this area have constrained their scope of research to exploring the links between childhood trauma and men’s violence towards women (such as Gonzalez et al 2016, Teva et al 2020 and Fernández-Montalvo 2020).

Imagine you’re a researcher investigating the link between corporal punishment and intimate partner violence. You conduct a literature review and all the studies you unearth show a connection between men's childhood trauma experiences and perpetration of intimate partner violence in adulthood, and between women’s childhood trauma experiences and intimate partner violence victimisation in adulthood.

Perhaps you fail to notice that none of the studies asked about women’s perpetration of intimate partner violence, or men’s experience of victimisation. Or perhaps you notice it but assume that intimate partner violence is gendered, and therefore any link between childhood trauma and the perpetration of intimate partner violence by women or the victimisation of men by intimate partner violence is unlikely.

You publish an article in an online publication with a focus upon academic work with an extended readership of some 20 million, in which you claim, “There are gender differences in here too. Interestingly, some research shows girls who are smacked are more likely to grow up to become the victims of partner violence. Boys who are smacked are more likely to become the perpetrators.”

Your article is re-published by a science publication with a FaceBook reach of 625+ million readers. The article is promoted as follows:

Anyone coming across this article in their FaceBook feed would have probably incorrectly assumed that if girls and boys were both smacked1 during childhood, the boys would grow up more likely to be perpetrators and the girls would grow up more likely to be victims of partner violence: end of story. Boys would be no more likely to grow up victims and girls would be no more likely to grow up perpetrators. Otherwise the publication would have used gender neutral language, claiming, for example, that “children who are smacked are more likely to grow up to experience partner violence as adults (as perpetrators and victims).”

Incidentally the original study by Fulu and her colleagues found that mothers were between 13 per cent and 45 per cent more likely than fathers to smack the children in their household, depending on whether men’s reports or women’s reports were used.

What does the research say about the link between childhood abuse and intimate partner violence when both male and female participants are asked about their experience of childhood abuse and their experience of intimate partner violence as perpetrators and/or victims? Such research is harder to find due to the overwhelming research focus in the literature upon men’s violence towards women. However in 2009 Christy McKinney PhD and her colleagues published their study titled Childhood family violence and perpetration and victimisation of intimate partner violence: Findings from a national population-based study of couples in which they surveyed 1,615 couples from the US household population.

Their findings “provide new evidence that women and men exposed to childhood family violence are at increased risk of perpetrating non-reciprocal and reciprocal IPV compared to subjects with no history of childhood family violence, even after controlling for other factors. Our results also suggest childhood family violence is positively associated with being victimised by an intimate partner.”

More specifically, when it comes to gender, the researchers found that:

men who experienced childhood physical abuse were approximately four times as likely to perpetrate non-reciprocal male-to-female partner violence compared to those with no such childhood history

women exposed to child-family violence appeared to be more than twice as likely to be victims of non-reciprocal male-to-female partner violence compared to women without this childhood history

women who experienced child-family violence were more likely to perpetrate non-reciprocal female-to-male family violence than their counterparts

men exposed to child-family violence appeared more likely to be victims of non-reciprocal female-to-male partner violence compared to men without this history

men who experienced severe childhood physical abuse or experienced severe child-family violence were more than twice as likely to engage in reciprocal intimate partner violence compared to men with no history of childhood family violence; a male history of moderate child physical abuse or moderate child-family violence was also positively associated with an increased risk of reciprocal intimate partner violence

women who experienced severe child physical abuse or severe child-family violence were more than three times as likely to engage in reciprocal intimate partner violence compared to women with no childhood family violence history; all other forms of female childhood family violence were associated with a greater than 1.5-fold increased risk of reciprocal intimate partner violence.

In other words, children who are abused are more likely to grow up to perpetrate unilateral family violence, engage in reciprocal family violence, and be victims of family violence as adults. This is the story that should have been circulated.

Instead, as a result of gender bias in research and the use of carelessly misleading language, the myth has been widely circulated that boys who experience child abuse aren’t any more likely to be victims of intimate partner violence as adults than boys who don’t experience abuse as children. Likewise, the myth has been propagated that girls who experience child abuse aren’t any more likely to be perpetrators of intimate partner violence as adults than girls who don’t experience abuse as children.

More weight has been erroneously added to the dominant paradigm claiming that intimate partner violence is “gendered”. As a result, male victims and female perpetrators are less likely to receive the services and support they need. Couples who engage in reciprocal family violence (the most common form of family violence and the most damaging to children) are, as usual, ignored by the dominant paradigm, and are left to continue on in their dysfunctional and damaging relationships.

It’s important to note that everyone who contributed to this result may well have acted with good intentions. The original researchers exploring links between child abuse and violence against women probably didn’t intend for their research to be used in this way. The academic exploring links between corporal violence and intimate partner violence was accurate when she claimed that girls who are abused are more likely to grow up to become the victims of partner violence and boys who are abused are more likely to become the perpetrators. They are. It’s just that boys who are abused are also more likely to grow up to become victims of partner violence and girls who are abused are also more likely to become perpetrators. The publications who circulated the article were just doing their job disseminating new research to the public – they probably lack the resources to fact-check every article submitted for publication.

This case study is just one small example of the way in which the dominant “gendered violence” paradigm regularly ignores, downplays, diminishes, excludes and blames male victims of family violence. Because of this, many male victims still lack the services and support they so desperately need.

References

Fernández-Montalvo J, Echauri JA, Azcárate JM, Martínez M, Siria S, López-Goñi JJ. What Differentiates Batterer Men with and without Histories of Childhood Family Violence? J Interpers Violence. 2020 Sep 20:886260520958648. doi: 10.1177/0886260520958648. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32954956.

Fulu E, Miedema S, Roselli T, McCook S, Chan KL, Haardörfer R, Jewkes R; UN Multi-country Study on Men and Violence study team. Pathways between childhood trauma, intimate partner violence, and harsh parenting: findings from the UN Multi-country Study on Men and Violence in Asia and the Pacific. Lancet Glob Health. 2017 May;5(5):e512-e522. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30103-1. PMID: 28395846.

González RA, Kallis C, Ullrich S, Barnicot K, Keers R, Coid JW. Childhood maltreatment and violence: mediation through psychiatric morbidity. Child Abuse Negl. 2016 Feb;52:70-84. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.01.002. Epub 2016 Jan 21. PMID: 26803688.

McKinney CM, Caetano R, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Nelson S. Childhood family violence and perpetration and victimization of intimate partner violence: findings from a national population-based study of couples. Ann Epidemiol. 2009 Jan;19(1):25-32. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.08.008. Epub 2008 Oct 4. PMID: 18835525; PMCID: PMC2649768.

Teva I, Hidalgo-Ruzzante N, Pérez-García M, Bueso-Izquierdo N. Characteristics of Childhood Family Violence Experiences in Spanish Batterers. J Interpers Violence. 2020 Jan 9:886260519898436. doi: 10.1177/0886260519898436. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 31916483.

1 The original article was subsequently amended to read “Correction: this article originally stated girls who are smacked are more likely to be victims of partner violence later in life, while boys are more likely to be perpetrators. In fact, the evidence shows this is true of abuse more broadly rather than smacking. This paragraph has since been removed.” The re-published article was never amended.