Exciting new avenues for violence-prevention ignored so as to fit the gendered violence narrative

As someone working in the field of family violence prevention, I was interested to read Jane Gilmore’s latest article in The Age titled "This is why sexist jokes are dangerous." In it, Gilmore cites a recent study by US researchers Jennifer Ruh Linder and W. Andrew Collins published in the Journal of Family Psychology. Gilmore writes,

"Longitudinal research published by the Journal of Family Psychology found that while seeing violence between parents had a significant impact on the likelihood of boys using violence as adults, the attitudes of their friends when they were 16 years of age had an even stronger impact. These findings have been duplicated in many other studies and prove the point that poor attitudes to women and gender normalise and enable violence against women."

Reading Linder and Collins’ study, I was surprised to discover that not only had Gilmore gotten her facts wrong, she had ignored interesting and relevant findings from the study that could potentially reduce family violence (or, in Gilmore’s language, reduce "violence against women").

The study actually didn’t investigate the attitudes of boys’ friends when they were 16 years of age AT ALL. It found that "individuals who had higher quality friendships at 16 years of age reported lower levels of perpetration and victimisation in subsequent romantic relationships at 21 years of age", and "observed conflict management at 21 years of age was best predicted by friendship quality." In other words, when boys (and girls) have stronger peer friendships, they are less likely to become perpetrators or victims of family violence, and are more likely to resolve relationship conflict without the use of violence.

Gilmore was correct that the study found seeing violence between parents affected the use of violence as adults, but it didn't find that it increased the likelihood of boys using violence. Instead it found that at 21 years of age, witnessing of partner violence was associated positively with victimisation. As well as Gilmore getting this fact wrong, this wasn’t actually one of the most significant findings of the study.

The most consistent predictor of both perpetration and victimisation at 21 as well as 23 years of age was parent–child boundary violations at 13 years of age. Parent-child boundary violations was a combined measure of two other measures: seductive relationship and boundary dissolution.

"Seductive relationship rated behaviours occurring between the parent [usually the mother] and adolescent that usually occur only between romantic partners. Examples of such behaviours included intrusive physical contact, private jokes, and intimate or coy voices. Boundary dissolution referred to three types of intrusive or overly familiar behaviours: "spousification", in which the adolescent met the caretaking needs of the parent; "parentification," in which the adolescent displayed nurturance or limit setting as a parent would; and peer-role diffusion, in which both the adolescent and the parent acted in a manner similar to adolescents. Examples of such behaviours included signs of disrespect of the parent by the child, high levels of caretaking of the parent by the child, and avoidance of responsibility by the parent."

These parent–child boundary violations "had not been considered previously in research on relationship violence. Those individuals who experienced higher levels of behaviours such as casually seductive and role-reversal behaviours by the parent in early adolescence reported higher levels of physical perpetration and victimisation in their romantic relationships in early adulthood."

“In addition to the significant impact of boundary violations, negative parent–child interactions in adolescence also contributed to likelihood of later physical aggression. Negative interactions in the parent–child relationship at 13 years of age were positively associated with victimisation at 21 years of age. Individuals with a history of hostile, negative, and conflictual parent–child interactions were more likely to be victims in their romantic relationships.”

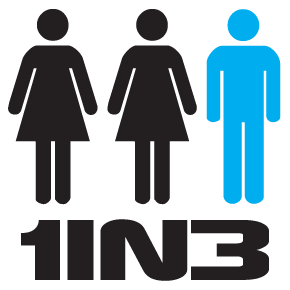

The study also found that at 23 years of age, childhood abuse was correlated positively with both perpetration and victimisation. It found, like most other studies, that most dating violence was bilateral. And finally, the study found that family violence was gendered, but not in the way Gilmore would like to think: at 23 years of age, male participants reported higher levels of victimisation than female participants.

The study provides exciting new avenues for further violence-prevention research.

"…The almost exclusive focus on early family violence as the primary factor in the likelihood of children’s later violent relationships provides an incomplete picture of the development of romantic aggression. Quality of parent–child relationship experiences in adolescence had predictive power above and beyond early family violence and was a more consistent predictor of physical aggression and conflict management. In addition, friendship quality was a key predictor of romantic aggression, especially of observable conflict management skills in romantic relationships."

It’s a great pity that it appears Gilmore’s ideological blinders caused her to fit the study’s actual findings into her pre-existing “violence against women” narrative so that she not only misled readers with major factual errors, but also missed out on disseminating the most exciting findings of the study that show great promise at reducing family violence.